‘Relational approaches’ are a collection of techniques and strategies which focus on nurturing relationships rather than managing behaviour.

Relational approaches offers professionals a perspective, a philosophy, and a framework for understanding children with social emotional and mental health needs. It offers a new way to look at behaviour and understand what promotes satisfying and sustainable relationships even under adverse conditions. Whilst behaviour management approaches seek to change the behaviour of another, the relational approach seeks to enable the other to change their own behaviour.

The approach has been tested and refined over more than a decade in an independent school set up by the charity Inaura in 2007 for children with complex needs for whom no alternative school setting could be found. The school has a non-coercive ethos and has never used permanent or fixed term exclusions punitively.

Relational approaches are a synthesis of best practices in working in school which share a core ethic of 'minimum coercion'. Although this presentation has been developed by Adam Abdelnoor its origins are ancient - in fact their roots stem from our earliest attempts at co-operation and social order.

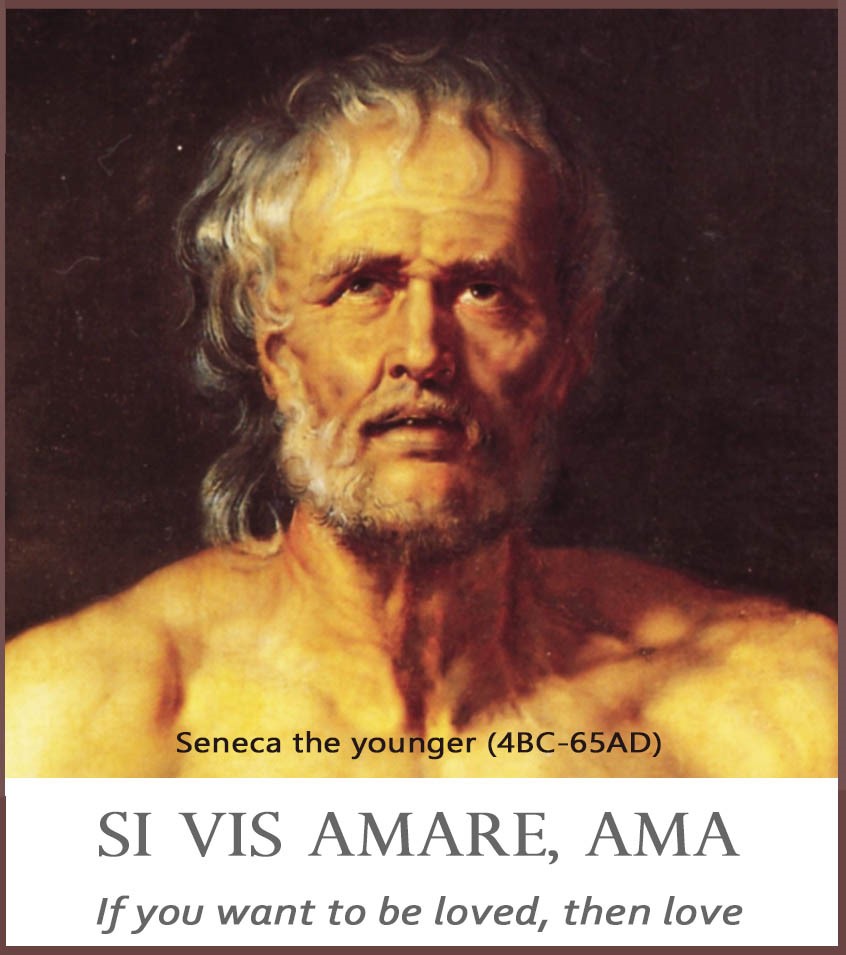

This enduring link with the past is illustrated by two quotes:

"If you want to be loved, love"

(Seneca the Younger, 4 BC – AD 65)

“If you want to be loved, meet needs”

(Abdelnoor the author, 2001)

It's hardly surprising then that the different elements of the approach rely on wisdom learned from others and this debt is acknowledged.

But the synthesis is coherent and original, and the seven-factor model for relationship growth which is at the heart of the approach is original to the author.

Adam Abdelnoor is a chartered psychologist and qualified teacher with 30 years’ experience in education who has worked with children at risk from exclusion since 1989.

He is the founding chief executive of the inclusion charity Inaura. His Churchill Fellowship in 2000 (Defining and developing zero school exclusion cultures) was followed by two British Academy Awards.

A broadcaster and writer, Abdelnoor’s publications and media work include Preventing Exclusions (Heinemann, 1999) and the Teacher TV series 'What did you do at school today?'

Adam founded Inaura school in 2007 and was its Headteacher for ten years. Inaura is a special school in Somerset for children with complex needs.

To understand the origins of the relational approach, the science and art of successful relationships, read on...

I’ve been a teacher all my life, in Year 1 through to Year 13 (and at University and Further Education level), and in all kinds of special schools.

I’ve seen first-hand the harm done by exclusion, and been required to apply tedious behaviour management frameworks which seem to work initially but become more formulaic and less effective over time.

I’ve seen the harm done by the chronic overuse of ‘sanctions’ or ‘consequences’, with their rigid tariffs and narrow focus.

I’ve tried numerous rewards systems, and discovered that children often choose to opt out of them… who needs a star, anyway?... or learn to manipulate them.

In one school I worked in, every room was supplied with a cassette tape player set to chime every three minutes. The idea was that children got a point for being ‘on-task’ when the bell chimed. We certainly taught the children to accurately estimate 2 minutes and 59 seconds… but not much else!

When I was nine I attended Adamsrill Primary school. The Headteacher Mr Goode was a kindly man and a firm disciplinarian. On Thursdays in assembly he read to us from Pilgrim's Progress. On Fridays he meted out punishment to any boy who had been... naughty? bad?... I can't remember the word we used for it.

The boys had to come out to the front of assembly and were given six strokes with the cane. Mr. Goode would put his foot up on his wooden chair and haul the kids over his knee.

On this particular day I suddenly noticed something which shocked me. Week after week it seemed to be the same boy who was punished.

I said to myself, this cannot be right. Whatever this is supposed to achieve - it isn't achieving it!

I've been asked many times why I care about troubled children. I have no personal axe to grind, you see. And in the end, this is the best reason I can come up with.

At the special school in Brixton where I learned my basics, we were always required to apply behaviour policies rigorously - as with all behaviour systems consistency and firmness were considered essential. The search for the holy grail, the perfect child management technique, was interminable.

I came to despise behaviour management scripts. You may have used this sort of thing yourself. “You are now on step one, are you choosing to stay on-task or are you choosing a 3-minute time out?”. Step 7 was “leave the premises or have the police called”. I never got that far!

Step 3 led to the child being sent upstairs to the quiet room for an hour. Now, the quiet room had south-facing windows looking out over the garden. Tony, the quiet room supervisor, didn’t ask much of the children provided they were calm and quiet. Sometimes, there were polo mints!

Some of my class discovered how easy it was to escape the curriculum and enjoy a bit of peace and quiet. All it took was a few carefully timed FOs and FUs. I knew what was going on but had been directed to apply the policy without deviation.

Later, I discovered that other class teachers had simply ignored the directions. One had shown his pupils the brand new mountain bike in his stock cupboard and told them the best-behaved student would be given it at the end of term!

The PE teacher’s approach was even more direct. He caught up with the pupils who had misbehaved in the corridor and gave them a dead leg or a cuff round the ear. He was a brute who bullied the staff as well as the students.

The last straw was being criticised for sending children to the quiet room too much. I resolved to ditch the behaviour policy myself. That was the start of the best times!

On the day after I was trashed in the staff meeting for sending children out of class too much, I decided to blow my students' tiny minds!

I announced THE GOOD NEWS! I would much rather be in the class with them in the staffroom. So I was giving up my breaks and lunchtime forthwith.

They no longer had to do their work during class time because if they hadn't finished they could do it at break or lunchtime - or even after school finished. I told them I would write to their parents and explain that if they needed to stay I would drive them home afterwards.

From now on, I said, if there were behaviour problems in class we would deal with them together in class. No steps and no quietroom - we would have a nice quiet room right here!

Of course they called my bluff - but discovered I was not bluffing! After a couple of break-time work sessions it just stopped being an issue. I never had to drive any child home.

Along with this new class policy, I changed my tone completely. My children had become my colleagues, in effect. I needed their help to get the teaching and learning done.

So I treated them as moral equals. We didn't have equal roles or competencies but we were humanly equivalent.

I didn't have more power than them, just different powers. I could sanction, they could throw a chair.

We used to have this thing called mutually assured destruction, or MAD, for short. Now that we were working co-operatively, trying to coerce the children seemed like, well, MAD...

I had observed that the pupils were much more co-operative when they were with staff they liked. I decided that my policy would be to make the children like me so much they would do anything I asked!

But if Seneca is right then this could best be achieved by liking the children as much as possible. Could it really be that simple?

Yes!!

The year that followed that point in time was the happiest I had known in the school. The Headteacher continued to harass me, but had very little to go on now. None of my students ever heard the script again. We didn’t need it, to be honest. Sometimes I had a second class foisted on me - two classes to manage, without support. No problem!

Look, it was uncanny… but what was it I was doing (or not doing)? My enquiring mind wanted to be able to give a name to it and to understand why it worked.

In the beginning, I’m not sure I even realised I was using a restorative approach. But I was clear about one thing: Relationships are of the first importance. My book ‘Preventing Exclusions’ (Heinemann, Oxford) is based on that principle.

My first direct contact with restorative conferencing was as a family group conference facilitator for Haringey Social Services, the first LA in the UK to offer this service.

I quickly became immersed in the philosophy and psychology of restorative practice and began to integrate into my work with children in schools, learning and applying the approach through three years of research, which took me to Belgium, New Zealand, Canada, the USA, and Winchester in England, where I met Marshall Rosenberg.

Marshall Rosenberg’s Nonviolent Communications method fitted perfectly with a restorative approach.

The keystone of effective restorative activity is the facilitation of restorative dialogue between people who, if they had had great communications skills, would probably not have needed a facilitated restorative process.

Marshall’s approach is to continuously reshape the dialogue to reduce tension and alienation.

I've learned his method and then developed it for an educational context. I hope I have extended its applicability by doing so.

When I started the charity Inaura in 2000 its main objective was to make school exclusion obsolete as a school management process.

That’s another story, but it was the charity’s activities in Somerset which led to the foundation of Inaura independent special school for children with complex needs, who were often also children in care, struggling with attachment difficulties.

I was the school’s Head throughout its first decade. We determined that the school would apply a relational approach, a non-coercive ethos. That obviously meant no punishments.

In this context, an alternative method for minimising social harm was essential and so we turned to restorative approaches. No children were excluded from the school during my time there.

The approach works because of the personal integrity and social awareness of the people applying it, not because the method can be turned into a list of ‘magic bullets.’